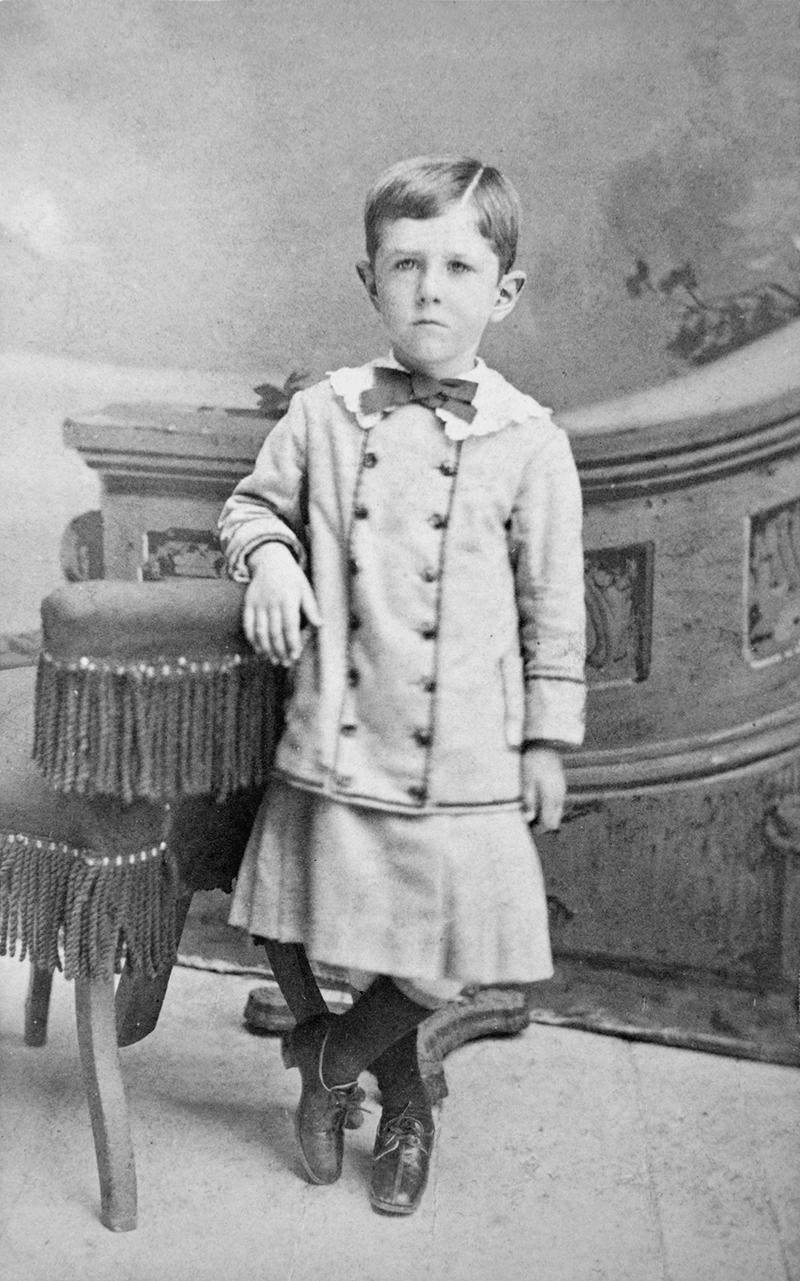

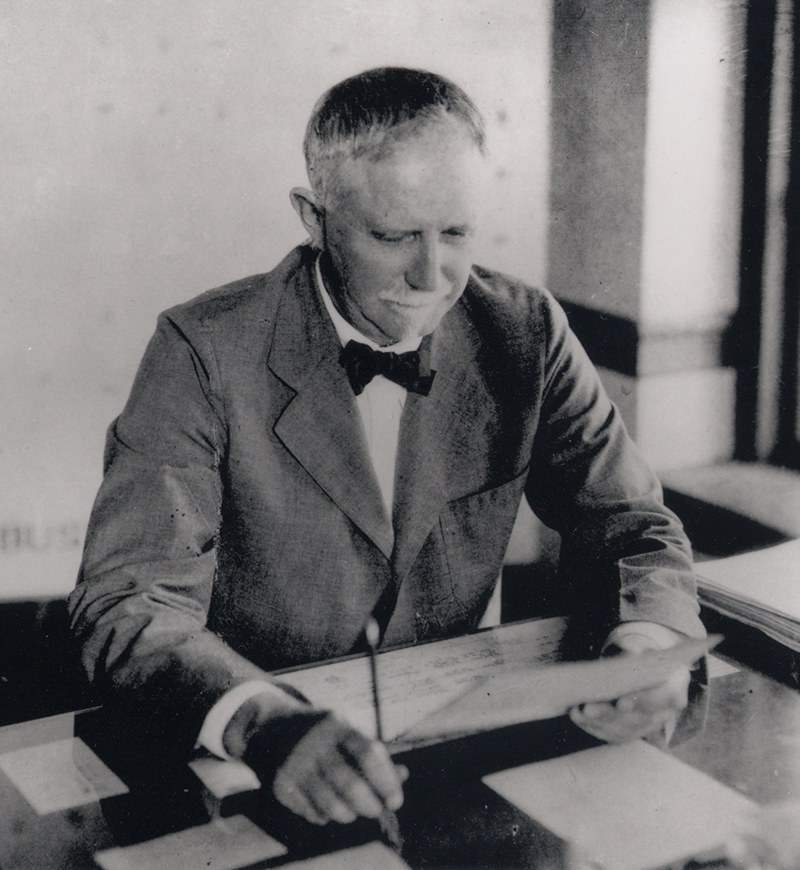

Roger Ward Babson (1875–1967)

“To most boys, summers spent dropping off bundles of dry goods to country stores and listening to the small talk of their owners would seem a pale substitute for the joys of baseball or the swimming hole; to Roger, they were his initiation into the world of business, which even at this early age intrigued him.”

– John Mulkern, Continuity and Change: Babson College, 1919−1994.

Throughout the Years

The Babson Ancestry

Representing the 10th generation of Babsons to live in Gloucester, Mass., Roger Babson valued his heritage. He researched his ancestors, investigating their personalities, professions, and lifestyles. Beginning with Isabel Babson, who came to Massachusetts from England in 1637, Roger discovered a lineage of farmers, merchants, midwives, religious preachers, and sea captains. Believing that personality traits were hereditary, he continually looked for opportunities to foster and benefit from his ancestors’ individual attributes.

Educating Roger Babson

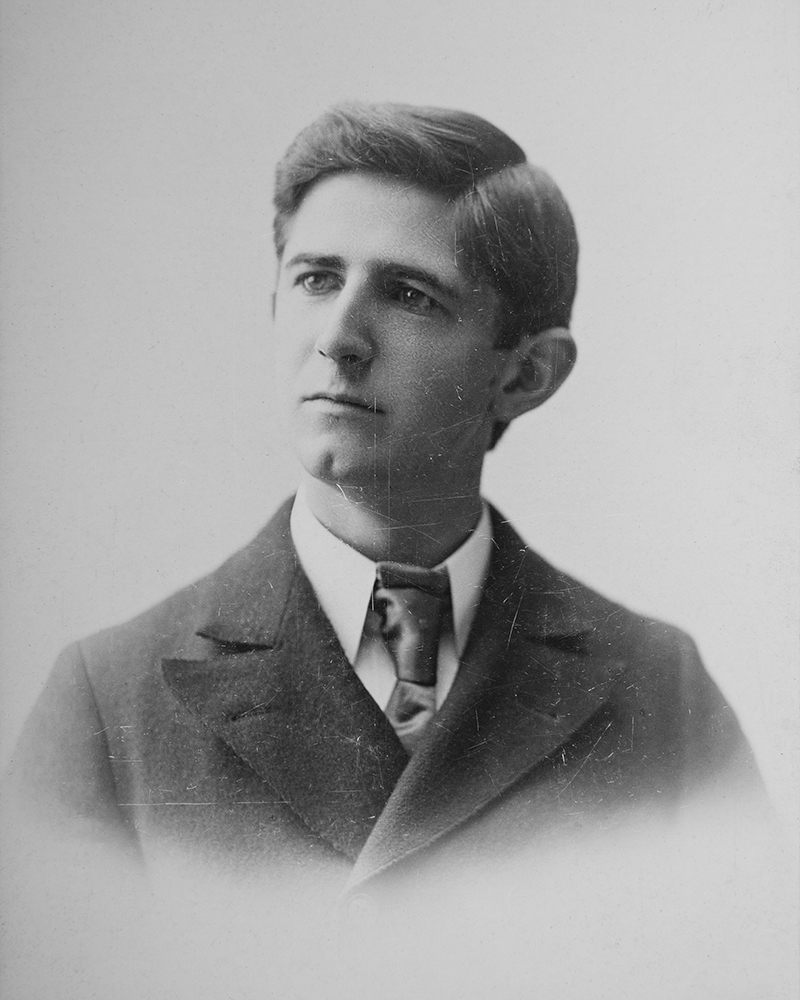

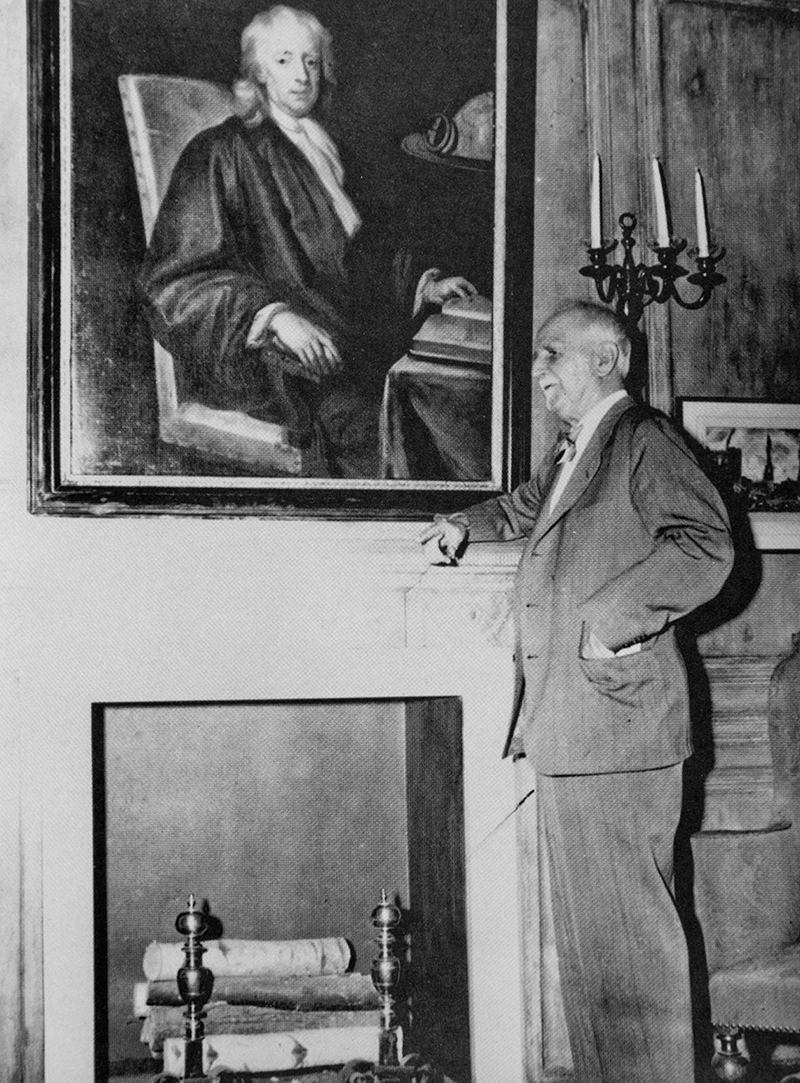

Roger also valued lessons from his childhood, especially the business and investment practices he learned from discussions with his father, Nathaniel Babson, who owned a dry goods store. Despite Roger’s interest in business, his father had little faith in colleges and their academic programs. Against Roger’s wishes, Nathaniel decided his son would pursue a rigorous, technical education at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Feeling that the instruction “was given to what had already been accomplished, rather than to anticipating future possibilities,” Roger believed that his professors had failed to foresee the great industries of the 20th century: automobiles, aviation, motion pictures, phonographs, and radios. The one aspect of his studies at MIT (1895–1898) that he valued throughout his life was learning about the British scientist, mathematician, and philosopher Isaac Newton. Roger was impressed by Newton’s discoveries, especially his third law of motion—“For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” He eventually incorporated Newton’s theory into many of his personal and business endeavors.

Business Beginnings

While on break from MIT, Roger applied his engineering studies to various highway projects throughout Massachusetts. Upon graduating in 1898, Roger knew for certain that he preferred an alternative career. Nathaniel Babson counseled Roger to find a line of work that would ensure “repeat” business indefinitely. After careful consideration, Roger decided to try the world of finance and looked for work as an investment banker.

In 1898, Roger began his business career working for a Boston investment firm where he learned about securities. Inquisitive by nature, Roger soon knew enough about investments to get himself fired. Acting in the best interests of his clients, he had questioned the methods and prices of his employer and quickly found himself out of work. Roger subsequently set up his own business selling bonds at competitive prices in New York City and then in Worcester, Mass. By 1900, he had returned to Boston to work once more for an investment house and in March of that year, he married Grace Margaret Knight and moved to Wellesley Hills, Mass.

A New Lease on Life

In the fall of 1901, Roger contracted tuberculosis. His doctors initially told him that a cold “had settled on his lungs.” When Roger demanded to know the exact nature of his illness, he was given a decidedly gloomy prognosis. The tuberculosis had seriously affected one lung and had begun to attack the other; it was not certain if he would survive. For Roger, resignation was not an option. Demonstrating his characteristically dogged determination, he resolved to fight the disease and live a productive life. Rather than seek a “fresh air” cure in the milder climates of the American Southwest, Roger remained in Wellesley Hills. Cared for by Grace, a nurse by training, Roger gave a great deal of thought to how to continue his investment career away from a city environment. He ultimately decided to start a business based upon his investment expertise. While Roger finalized his business plans, Edith Low Babson, Roger and Grace’s only child, was born December 6, 1903.

Wall Street Comes to Wellesley

Aware that every financial institution employed statisticians who duplicated one another’s research efforts, Roger chose to develop a central clearinghouse for information on investment information and business conditions. He would publish his analysis of stocks and bonds in newsletters and sell subscriptions to interested banks and investors. In 1904, with an initial investment of $1,200, Roger and Grace founded Babson Statistical Organization, later called Business Statistics Organization, then Babson’s Reports, and still later Babson-United Investment Reports. As pioneers who helped revolutionize the financial services industry, the Babsons and their organization realized millions of dollars in annual revenues in the company’s first decade.

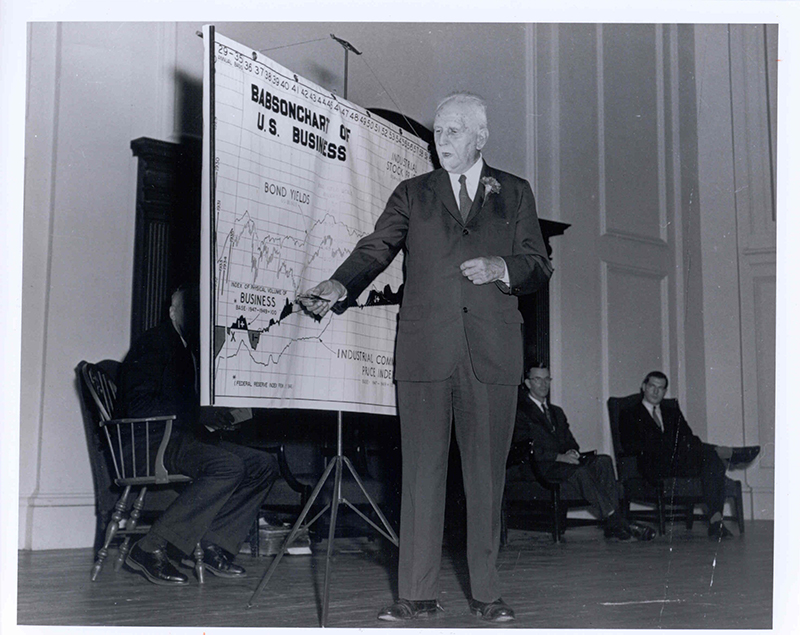

Pass It Along

Having amassed a sizable fortune, Roger was not content to join the idle rich. Instead he shared his business knowledge to protect investors, and invested his own wealth in industries and endeavors that would benefit humanity. After witnessing a dramatic stock market crash and financial panic in 1907, Roger expanded his investment practice to include counseling on what to buy and sell as well as when it was wise to purchase or unload stocks. Working with MIT Professor of Engineering George F. Swain, Roger applied Isaac Newton’s theory of “actions and reactions” to economics, giving rise to the Babson chart of Economic Indicators, which assessed current and predicted future business conditions. Although the Babson chart has since proved to be an imperfect tool, through it Roger earned the distinction of being the first financial forecaster to predict the stock market crash of October 1929.

Roger extended his interest in the public’s welfare beyond investment counseling. He encouraged industries to develop products to improve public health and safety. Among businesses receiving Roger’s approval and financial backing were select manufacturers of sanitary paper towels and other hygienic products, fire alarm call boxes, fire sprinklers, and traffic signals.

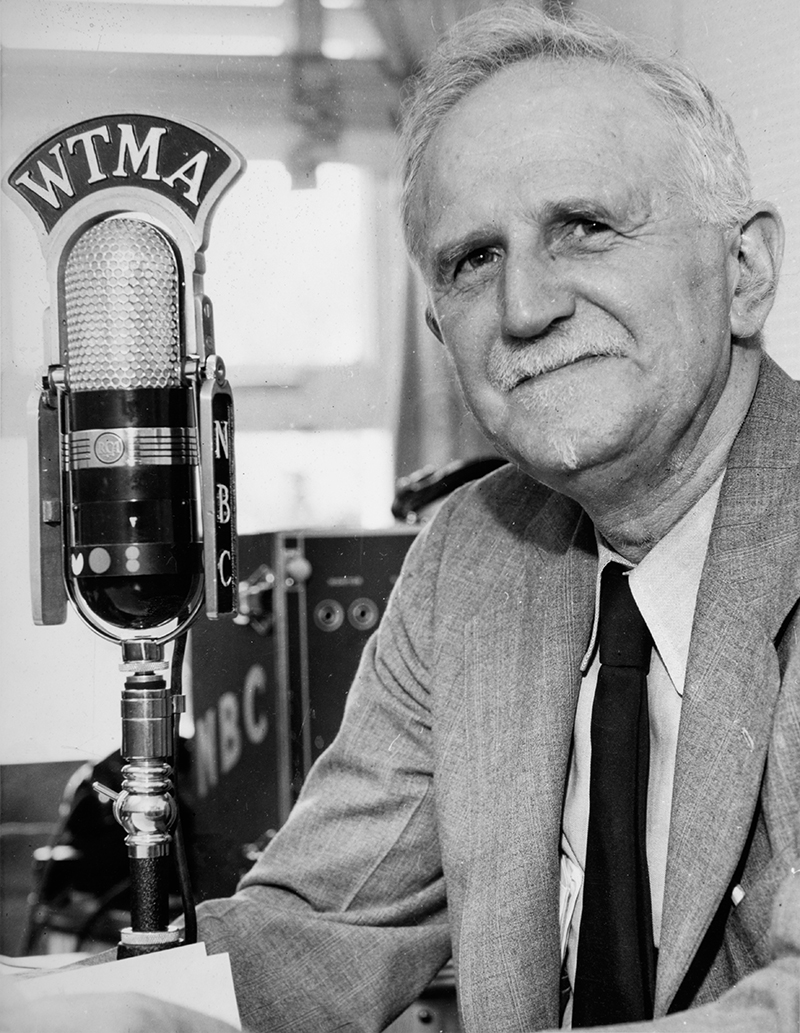

Roger saw it as his duty to share his insights and experience. An avid reader and writer, he sought to dispense his brand of advice and wisdom beyond the readership of Babson’s Reports. From 1910 to 1923, he commented on business and other matters as a regular columnist for the Saturday Evening Post. He also contributed weekly columns for the New York Times and for the newspapers owned by the Scripps Syndicate. Roger eventually formed his own syndicate, the Publishers Financial Bureau, to disseminate his writings to papers across the United States. During the course of 33 years, he wrote 47 books, including his autobiography, Actions and Reactions. Although his writings covered topics as diverse as business, education, health, industry, politics, religion, social conditions, and travel, the primary message behind each work was that individuals and society could and should change for the better.

The Babson Legacy

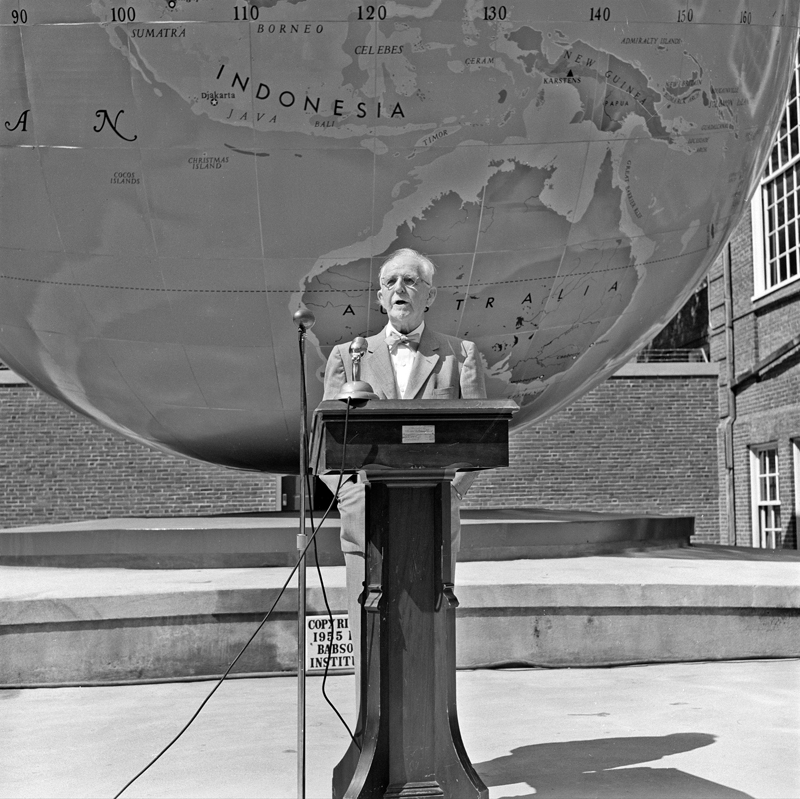

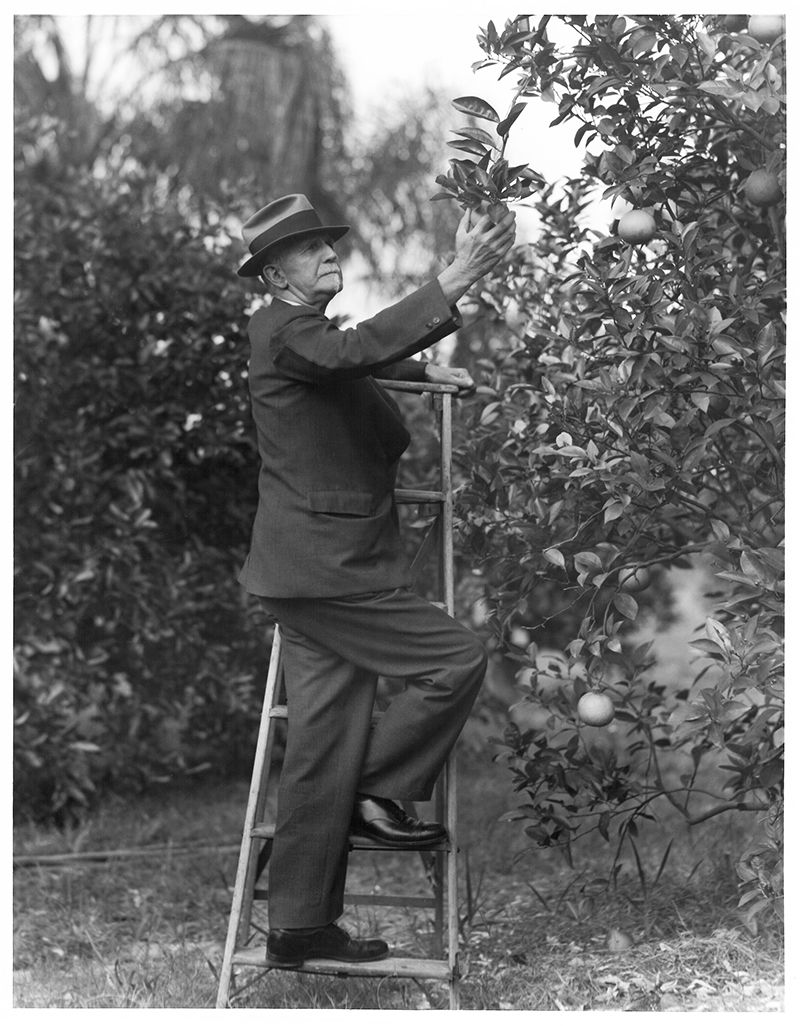

Babson College continues to be one of Roger’s greatest achievements. Remaining close to his initial conception of offering practical business and management instruction, the College now offers graduate business degrees and courses in executive education in addition to a four-year undergraduate business program. Roger’s success with Babson led him to establish Webber College in Babson Park, Fla., in 1927. Named after his granddaughter, Camilla Grace Webber, the college initially provided business education to women, similar in many ways to the courses at Babson. Webber College is now a coeducational institution, Webber International University. To bring practical business instruction to other parts of the United States, in 1946, Roger established a two-year, certificate-granting school, Utopia College, in Eureka, Kan. Utopia College graduates were invited to complete their baccalaureate degrees at Babson. Utopia College closed in the early 1970s.

Following Newton’s law of “actions and reactions,” as one venture in Roger’s life concluded, a new endeavor naturally began. He was never discouraged by setbacks. One of his greatest assets was his willingness to take chances and to rebound when risks overshadowed outcomes. In addition to his pursuits in education and business, Roger actively engaged in religion, politics, and scientific advances.

According to Roger, the greatest experience of his life was his religious conversion at the age of fifteen. Indeed, an unshakable faith in God was one of his primary personal beliefs. From 1936 to 1938, Roger served as national church moderator for the General Council on the Congregational-Christian Churches (later known as the United Church). During his term, he forced the council to examine itself and its weaknesses as he continually pushed himself, his business colleagues, and the students who studied at Babson. Using statistics, Roger showed that church development and attendance followed a cyclical pattern that was similar to business trends. He feared that the declining interest in religious activities was a clear and accurate indicator of the declining moral state of society. His appeals to chart a more morally correct course for the church, and for society, were met with defiance and personal threats. Roger’s tenure as moderator ended in great disappointment.

Not one to give up easily, Roger turned his attention to the promotion of an “Open Church.” Through a volunteer network, church doors would be unlocked every day, all day, so that persons of any faith could pause for private worship within the spiritual and curative sanctuary of a church. This experiment began in Wellesley in 1938; by 1942, the national Open Church Association was incorporated with its headquarters in Roger’s ancestral home of Gloucester.

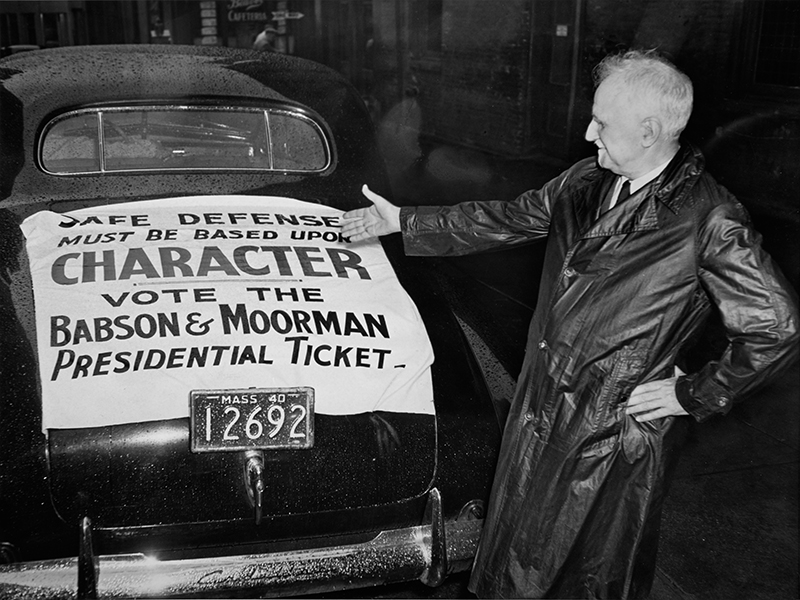

Roger’s convictions also extended into the world of politics. In 1940, he ran for President of the United States as the candidate for the National Prohibition Party. Although the church-affiliated party was best known for wanting to outlaw vices such as alcohol, gambling, and narcotics, as well as indecent movies and publications, the party also advocated reducing debt and taxation, conserving natural resources, aiding farmers, and “assuring workers and consumers a fair share of industry’s products and profits.” Although Roger knew his party would not win the election, he felt it was his duty to bring its moral and religious agenda to the nation. Out of a field of eight candidates, Roger followed third behind Franklin Roosevelt and Wendell Willkie.

Another risk that Roger took, although he was often ridiculed, was to promote research on gravity. Believing that the scientific community had done very little to expand upon Isaac Newton’s studies of gravity, he created the Gravity Research Foundation in 1948. Roger maintained that a conductor could be built, along the same principles as a waterwheel, for harnessing gravity waves as they occur in nature. He hoped that the invention of a perpetual motion machine would solve the world’s dependence on nonrenewable fuels. The nonprofit foundation, which still exists today, encourages research and acts as a clearinghouse for studies on gravity.

Throughout his long life and his many enterprises, Roger Babson was able to successfully foresee and foster change while holding fast to fundamental spiritual and ethical values. As a devoted educator, he saw it as his mission to pass along the basic truths that he learned from experience:

“It is not knowledge which young people need for success, so much as those basic qualities of integrity, industry, imagination, common sense, self-control and a willingness to struggle and sacrifice. Most individuals already have far more knowledge than they use. They need inheritance and development of a character which will cause them properly to apply this knowledge . . . Real business success comes through the qualities above mentioned, not through money, degrees, or social standing.”